We were thrilled to be able to talk about our work at the American Women of Science Symposium #BecauseOfHerStory on October 22, 2020. We’d like to tell you a little more about the work we presented and some of what we are planning next. Our slides and data are on Figshare, but we also wanted to give some more context for the work we did.

This project is inspired by the Funk List. The Funk List is a crowd-sourced list of Smithsonian women in science that was started in part by Vicki Funk, a senior scientist and curator of botany at the National Museum of Natural History. The purpose of this list is to start the process of improving the presence of Smithsonian women online and make them more well-known. Vicki circulated this list to Smithsonian science units and departments and asked them to add the women that have been part of their branches of the Smithsonian since its beginning in 1846. Vicki unfortunately passed away a year ago, and after her death, the list was named in her honor. Since that time, Liz Harmon, American Women’s History Initiative Digital Curator has been continuing to add new women in science and the list is now at more than 400 women! Vicki was a collaborator and mentor of Rebecca’s and this photo by Mauricio Diazgranados captures her spirit so well. She inspired so many women to continue on in science and to keep pushing for change.

Figure 1. Photo of Vicki Funk by Mauricio Diazgranados.

Measuring Scientific Impact

When we set out to work on this project, we started thinking about how we measure scientific impact. While there are obvious metrics like the number of peer-reviewed scientific papers, or discipline-specific awards, there is also service, public outreach, mentorship, and in particular for the Smithsonian, impact on the collections. Women in science often bear a larger burden of service and mentorship, which doesn’t often result in career advancement, even though they are essential for scientific progress and growth.

We will show initial results from two different data sources. First, the Smithsonian Annual Reports are just that, documents published annually, which give highlights of the Smithsonian year. Transcriptions of these going back to 1846 are available through the Biodiversity Heritage Library. We are using mentions in these reports as one measure of scientific impact. If someone is mentioned in an annual report, then something they did that year was notable to Smithsonian leadership.

Figure 2. Title pages of the 1972 Smithsonian Annual Report.

Methods & Results

We are also using Smithsonian Research Online or SRO, maintained by Smithsonian Libraries, which has all the citations for publications by Smithsonian authors. We were able to pull the data for each of the women on the Funk List via the SRO API.

We used a combination of natural language processing in spaCy and shell scripting to:

- Extract and count mentions of women on the Funk List in Annual Reports

- Count publications for women on the Funk List from Smithsonian Research Online

- Extract and count occurrences first names and words related to science in the Annual Reports

We decided to include all women from the Funk List that are no longer working at the Smithsonian and Annual Reports from 1846 up to and including 1999. Of the 127 women that remained, 12 are women of color, and one is a trans woman. We recognize that this list of 127 is already biased toward those most well-known around the Institution. It is our hope that by beginning to understand the level of visibility of these most prominent women in science, we will be able to start learning more about those never mentioned in the reports.

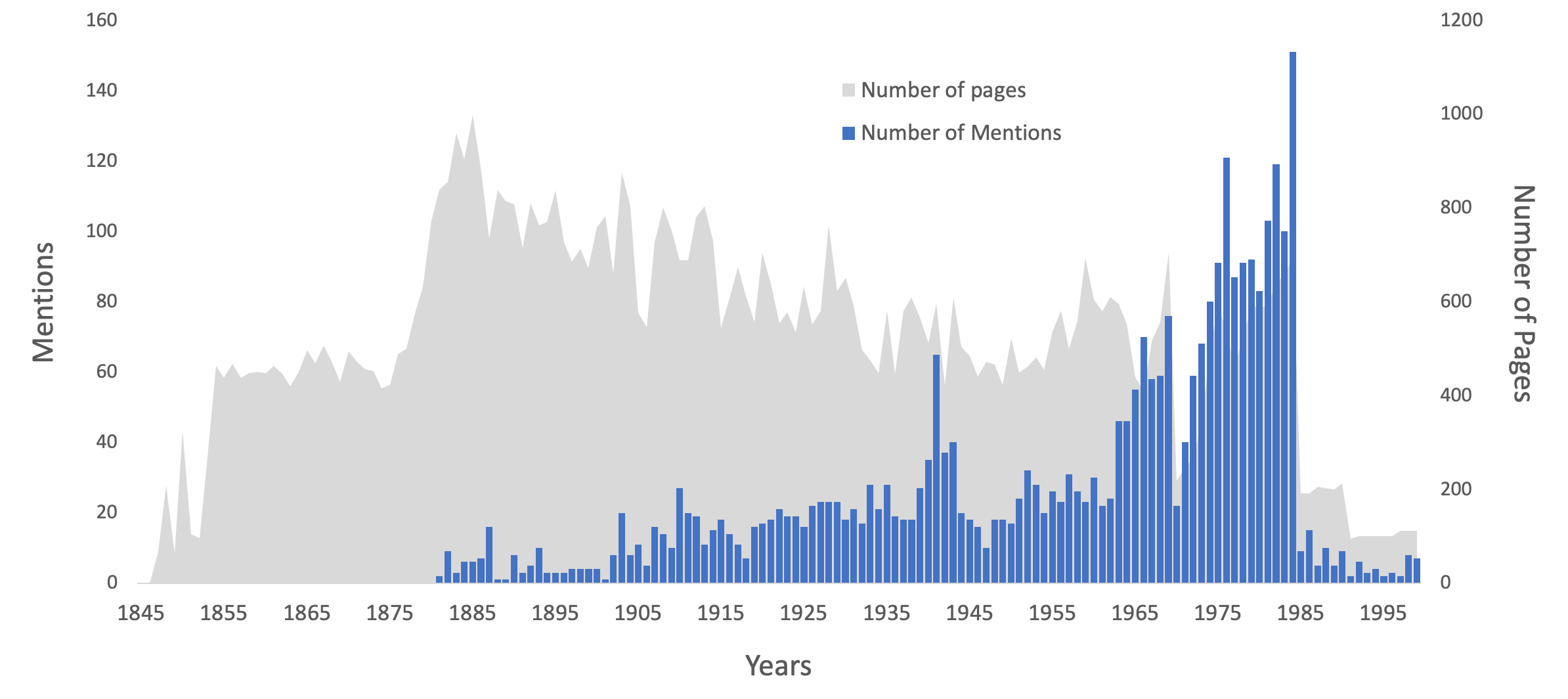

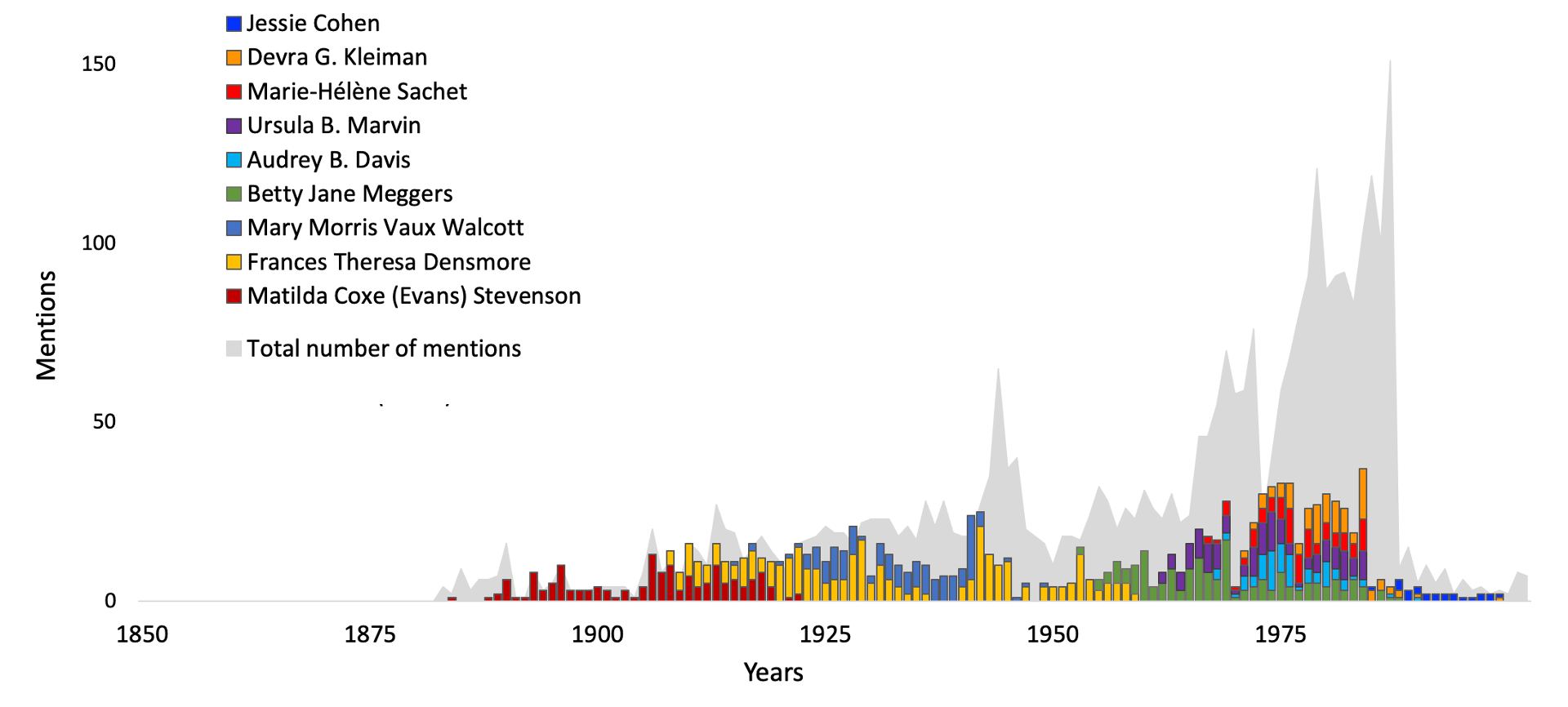

The first mention of a woman on our list was in the 1880 Annual Report. The number of total mentions increases steadily until 1984. Early in Smithsonian history, for example in the 1880s or 1890s, only one or two women from our list are mentioned per Annual Report. That number increases over time and it peaks in 1984, with 40 women being mentioned. There’s a sudden drop in the number of mentions in 1985, after which time the Annual Reports sharply decreased in length, from 694 pages in 1984 to 192 pages in 1985. Starting in 1991, the number of pages dropped again to around 100, and the reports also became much more visual. In the plots below, you can see the number of Annual Report mentions for all 127 women plotted over time, the number of Annual Reported mentions with the most-often mentioned women in each decade highlighted, and the publication counts plotted against the count of Annual Report mentions.

Figure 3. Mentions in Annual Reports with overall page count.

Figure 4. Mentions over time with top women per decade.

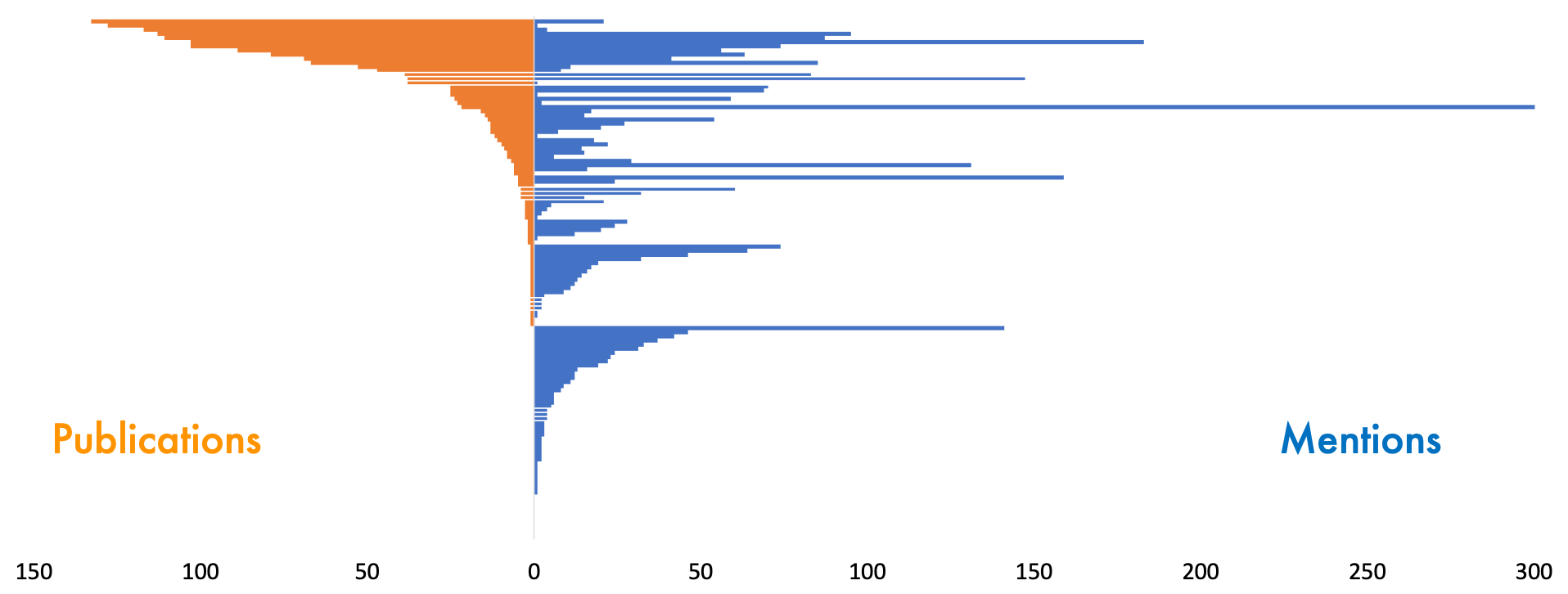

Figure 5. Publication count plotted against mention count.

Who are the most prominent SI women in science?

As you can see, the women with the most Annual Reports mentions are not necessarily those with the most publications. The three most mentioned women are Frances Theresa Densmore, Betty Jane Meggers, and Matilda Stevenson. All three were members of the Anthropology Department at the National Museum of Natural History. The most published woman from our list is Vicki Funk. Vicki published 133 papers up to 1999, which is the end of the time span for our analysis, but if we account for all her publications until her death in 2019, that number jumps to 368. Other highly-published women are JoGayle Howard from the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute and Pamela Vandiver, from the Museum Conservation Institute. Pamela Vandiver had 128 publications but only one Annual Report mention.

Figure 6. Photos from SIA of Funk, Howard, and Vandiver.

Figure 7. Photos from SIA of Densmore, Meggers, and Stevenson.

Who are the most prominent SI women in science by decade?

We started with 127 women and looked across 150 years of Annual Reports. If we look decade by decade, there are nine women in science who appear as the most prominent throughout Smithsonian history in terms of their presence in the Annual Reports.

Matilda Stevenson was the most mentioned woman in the 1890s and early 1900s. She was from the Anthropology department at the National Museum of Natural History, and was the first woman employed by Bureau of American Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution, and the first president of the Women’s Anthropological Society of America. The National Anthropological Archives has more than 3300 photographs collected by Matilda.

Frances Densmore is the most mentioned woman in four different decades (1910s, 1920s, 1940s, and 1950s)! She devoted over fifty years of her life to the study and preservation of Native American music. She collected thousands of song recordings, including twenty-four hundred transcribed songs.

*In the 1930s, we have Mary Vaux Walcott. She was a botanical illustrator and a volunteer at Smithsonian. She was the wife of Charles D. Walcott, who was the fourth Secretary of the Smithsonian. Many times, Mary Walcott is simply referred to as Mrs. Charles Walcott, which complicates the task of giving proper attribution.

*In the 1960s, we have Betty Jane Meggers. She was a research associate in the Anthropology Department at NMNH, and her studies focused on South American cultures.

*In the 1970s, we have three women who were equally mentioned in the reports. Audrey Davis, from the National Museum of American History, Ursula Marvin, from the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory, and Marie-Hélène Sachet, from the National Museum of Natural History. It’s also the first time we have women with the title of Curator as a top-mentioned woman.

*In the 1980s, Devra Kleiman from the National Zoo, is the most mentioned woman in the Annual Reports. She helped create the field of Conservation Biology and her research helped save the Golden Lion Tamarin from extinction. She also helped change the way pandas were housed at the zoo, and thanks to her, Tai Shan, the first panda born at the National Zoo to survive longer than a few days was born in 2005.

*Finally, in 1990s, we have Jessie Cohen, a photographer at the National Zoo. She is represented in the reports by the images she captured of the animals and exhibits at the National Zoo. This also coincides with the reports becoming more visual, with images becoming more important to represent the most significant events of the year.

It is important to note that all of the women mentioned so far are white. There are also women who were firsts in their fields such as Sophie Lutterlough and Margaret Collins, both African American women, who have very few or no mentions in the data sources we considered. We have a lot of work to do in order to make their stories more central to Smithsonian science. The take-home message of our work is that we are just starting to scratch the surface of the women’s contributions at the Smithsonian Institution. We are beginning to understand the patterns and trends based on the notable women we know more about. We have not yet fully explored the context of the Annual Report mentions and how these may have changed over time. We also hope that by including more data sources in future work, we will be able to unveil new stories and give credit to those women that helped shape the Smithsonian history but are not as of yet well known.

A look at broad patterns in the Annual Reports

While our main question in this project was about women from the Funk List, we are also interested to learn more about how the Annual Reports have changed over time. Here, we present some very early work to that end. First, we were interested in knowing what were the most common first names mentioned in annual reports through time. These data are only instances where first names are spelled out, not just as initials, so it’s not complete first name data, but provides an interesting snapshot. Here are the top 10 names for each of 4 timepoints: 1920, 1950, 1970, and 1990. It is interesting, but perhaps not surprising, that these are all traditionally men’s names, and that out of 40 possible top names (10 in each year), there are only 16 total names. Men’s first names that were common in the 1990 annual report were largely the same names common in 1920.

Since there were no traditionally women’s names in the top 10, we thought we would explicitly look for the top 10 traditionally women’s names in the same 4 reports. We then counted the total number of mentions of these top 10 first names, and this is what you see plotted here. You can see that in 1920, about 10% of these total mentions are traditionally women’s names and by 1990, this percentage is slightly better, but nowhere near equal.

Figure 8. Plots of common first names in four different Annual Reports.

We can also look at word counts for particular words of interest across the reports. Here, we extracted the top 100 nouns for all the reports (stop words were removed). We plotted occurrences of different sets of words from this set of top 100 for each report.

- First, the words research and collections. As you might imagine, these are two of the most common words in the reports.

- We also looked at the words man, woman, male, and female. This was quite striking to, that woman occurs so rarely in the top 100 nouns across the Annual Reports. We have to do more work to understand the context of these mentions, but we do know that often the word man has been historically used in ways like: mankind, manned spacecraft, seemingly to represent all humans, in ways that are now considered exclusionary of women.

- Finally, we chose a set common science words and looked at their usage over time. Again, it will be interesting to look at the contexts for these mentions and how those have changed over time as science itself evolved and changed.

Figure 9. Word count of the words research and collection over time

Figure 10. Word count of the words man, woman, male, female over time

Figure 11. Word count of common science words over time

Conclusion & Acknowledgments

We hope that these initial peeks inside the Annual Reports at scale jumpstart more detailed study of women in science at the Smithsonian. We are excited to integrate these data with other collections and archives data to provide a fuller picture of Smithsonian science.

Data science is very collaborative work and we would like to acknowledge Effie Kapsalis, Liz Harmon, Mike Trizna, Tiana Curry, Megan Glenn, Grace May, Richard Naples, and Keri Thompson for their help with this project. We would also like to thank the Smithsonian Women’s Committee for funding.